Biodiversity means life. A look at a healthy coral reef shows what this means. Stable ecosystems have many different inhabitants of various species, each utilising even the smallest niches and depending on one another. Whether small or large, colourful or grey, plant or animal – the community constantly changes internally, but overall, it remains stable and is not easily thrown out of balance by external influences when it is healthy.

The importance of marine biodiversity

Stable marine communities provide vital services for humans: oxygen to breathe, food to eat, and protection from flooding. High biodiversity is essential for the proper functioning of an ecosystem. It makes habitats more productive and resilient against external threats, such as environmental changes.

High biodiversity ensures that a habitat can be used to its full potential. This is because different species have different requirements, such as light or temperature. For example, some algae thrive in bright light and grow best under intense sunlight, while other algae prefer lower light conditions within a habitat. They flourish best in the shade of the light-loving species. Together, they form a dense algae forest that provides much more food and shelter for marine life than a single species of algae alone.

The species in a community are not all equally abundant. Often, a few species dominate, while many rarer species exist that could not prevail in the selection process, but have not disappeared either. These species can play an important role during disturbances: if environmental conditions change, they suddenly have an advantage and can take on the role of the dominant species.

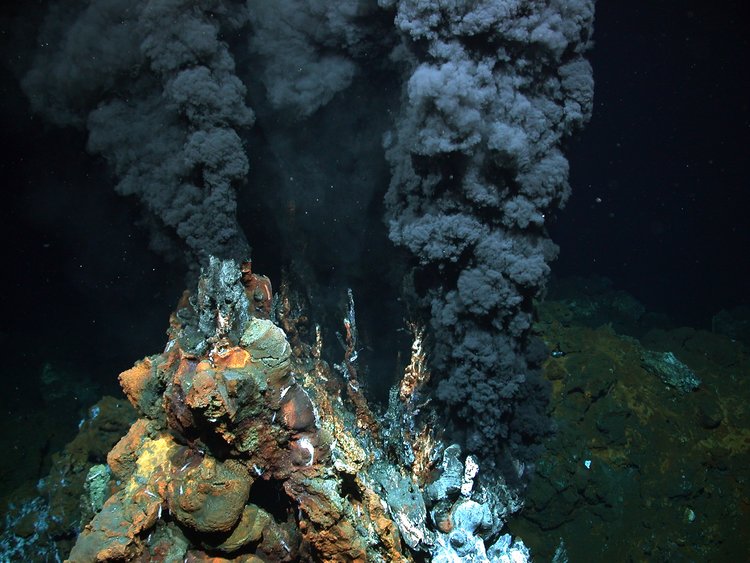

However, there are also some marine habitats with extreme environmental conditions, such as hot springs in the deep sea. The communities at such dark, hot places consist of relatively few species, but these species are perfectly adapted to the extreme conditions.

The communities of marine ecosystems constantly change internally. These processes of change are normal and ensure resilience. Therefore, it is entirely natural for species to migrate in and out, or in some cases, even become extinct.

When new species migrate

The migration of foreign species can have a significant impact on native communities and may even throw them off balance. However, not every newcomer is harmful: For example, the Japanese wireweed (Sargassum muticum), introduced into the North Sea, has integrated harmlessly into the Wadden Sea ecosystem. In contrast, the bristle worm Polydora websteri, native to Asia, drills into the shells of oysters and is therefore considered a shellfish pest.

Particularly dangerous are so-called invasive species. These are new species in a habitat that find no natural predators and can reproduce uncontrollably. In some cases, they reproduce so extensively that they claim all resources for themselves and displace native species. An example of this is the Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) in the North Sea.

Foreign species usually migrate in one of two ways: Most are unintentionally introduced by humans, for example, by attaching to ship hulls or by swimming in ballast water. Others migrate with warming water masses or benefit from newly constructed structures, such as wind turbines. Their foundation structures offer various organisms a suitable place to colonise a new habitat that did not exist before.

Research results from the North and Baltic Seas show how dynamically marine communities can react to newcomers and are often enriched by them. However, there are also clear losers in species shifts. On one hand, there are species that cannot withstand the competition from newcomers and are displaced. On the other hand, the new species can also introduce unknown diseases into the habitat and transmit them to the native individuals. If these natives do not have their own defense mechanisms or cannot develop them, they die in large numbers and disappear from the habitat.

Species extinction - quite natural in small numbers

The changing processes of ecosystems also include the extinction of animal and plant species. It is a natural part of the evolution of life on Earth. When a species disappears, new or other species usually take over its roles and functions. However, this adaptation takes time. The mechanism works well as long as the extinction rate remains within a normal range—meaning that no more than one in 10,000 species goes extinct within 100 years.

If the number of disappearing species rises far beyond this threshold, the world heads toward a mass extinction. This term refers to periods in which around 75% of all living species vanish within a short geological timeframe (usually less than two million years) without other species filling the functional gaps they leave behind. The last mass extinction occurred 66 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period when the dinosaurs disappeared.

The sixth mass extinction

The sixth mass extinction in Earth's recent history is currently looming. Due to human interventions in nature and the Earth's climate, the extinction rate has increased 100 to 1,000 times compared to pre-human times. Around one million species are currently at risk of extinction, and many species can no longer be found in parts of their original habitats.

The ocean is also on red alert. New research confirms that if temperatures in the atmosphere and the ocean continue to rise, species losses due to heat stress and oxygen depletion in the ocean over the next 75 years will be as severe as those caused by overfishing, pollution, and habitat destruction. In total, if global temperatures rise by up to 4.9 degrees Celsius by the end of this century, so many marine species would disappear that the conditions for a mass extinction would be met.

To preserve marine and ocean ecosystems and maintain biodiversity, effective ocean management is essential. Marine protected areas must not exist only on paper—the enforcement of regulations must be monitored, and violations must be sanctioned. Only then do we have a chance to prevent a mass extinction.

- Begum, T. (2023). What is mass extinction and are we facing a sixth one? Natural History Museum. www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/what-is-mass-extinction-and-are-we-facing-a-sixth-one.html (abgerufen am 02.11.2023).

- Penn, J.L. & Deutsch, C. (2022). Avoiding ocean mass extinction from climate warming. Science 376, 6592. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/science.abe9039.